Realms of Gold and Granite

|

| Bertha Mahony Miller in 1929 |

The Bookshop for Boys and Girls was born, in a twelvemonth, with a pedigree and a distinguished list of patrons. Its role was largely determined from the outset.

But life, real life, is also a string of accidents. Bertha Mahony was thirty-three and restless after ten years as a good right-hand at Boston’s Women’s Educational and Industrial Union when she came upon the article in the August 1915 Atlantic Monthly that, as she often said, “changed my life.” With a mix of statistics and soft soap, the author extolled bookselling as a new profession for the educated, emancipated woman.

Mahony, a serious, ambitious reader, would have liked to study librarianship years earlier at the new Simmons College, but lack of sufficient funds steered her toward the shorter secretarial course instead. As Assistant Secretary at the Union, a model of privileged progressivism, she had charge of promotional materials, in addition to her regular duties, and on her own initiative she launched a four-year series of children’s plays. Meanwhile, working with the Officers, she learned how people of influence get things done: by going to the top.

The eager bookseller-to-be scouted locations, considered and discarded the Northwest (reputedly like New England but too far away), resolved to remain in Boston despite its abundance of book-shops, and decided that hers would be a children’s bookshop — a new thing and a good thing.

By mid-October she had the backing of the Officers and Board of the Union, and a target date. She arranged a private, Saturday-morning tutorial in children’s literature with Alice Jordan, the Boston Public Library expert, and besides reading the assigned books, she studied the library booklists Jordan gave her, the compilations of Caroline Hewins and Clara Hunt. By spring, she and her newly recruited assistants were ready to place orders and Mahony herself was ready to meet the people who mattered. Bookseller and children’s-book enthusiast Frederic Melcher initiated her into the trade in Indianapolis and into the activities of the American Booksellers Association at its Chicago convention. Back East, she introduced herself to Anne Carroll Moore in New York and took a second, closer look at the Central Children’s Room; braved the elevated subway to see Clara Hunt in Brooklyn; and stopped off in Hartford to get Caroline Hewins’s blessing. “It was on this occasion,” Mahony later wrote, “that Miss Hewins promised to write for our recommended purchase list a preface on John Newbery’s ‘Juvenile Library,’ a first bookshop for children in London of the 1700’s.”

Had she asked? Had she known enough of Newbery’s historical role to ask? Had she already been thinking of her bookshop, five months before its scheduled opening, as another landmark in children’s book history? Or had this ardent young woman, with her plans for promoting books as selectively and creatively as Hewins and other librarians, and her undoubted enthusiasm for Hewins’s own celebrated list, touched a sympathetic chord?

|

| Elizabeth Whitney Field |

THE BOOKSHOP OPENED on schedule on October 9, 1916, in second-floor quarters adjacent to the Union but remote from the street. There, Mahony and her close associate Elinor Whitney and their staff promoted children’s books brilliantly, with a variety of programs, exhibits, and special services, and a handsome, 110-page booklist, with the Hewins preface, that was free to all comers and all correspondents. But in the aggregate not many books were sold. Was the location solely to blame or was the concept somehow questionable? In 1921, when a larger, street-front space became available next door, adult books were sold on the ground floor and the spacious, wrap-around balcony became the new and better staging-ground for children’s books. The sign over the door now read, cunningly: The Bookshop for Boys and Girls — With Books on Many Subjects for Grown-Ups.

According to Eulalie Steinmetz Ross, Mahony’s biographer, she had decided that “a children’s bookshop per se was not theoretically sound, isolating young readers as it did from the main stream of literature.” Maintaining that children’s books were part of the literary mainstream was an article of faith with Mahony, her contemporaries and successors, so she would probably not have demurred. But offstage, in a letter, her explanation is more acute: “People want to take care of their own book needs while shopping for their children, but more important still, the children themselves like the presence of grown-up books in a nearby space.” Mahony understood and appreciated people.

|

| Children browsing in the Bookshop for Boys and Girls in its first location |

For the future of children’s books, no less, it mattered. During the Bookshop’s first Christmas, Anne Carroll Moore stopped by with Caroline Hewins to look over the premises before she gave Mahony her support, privately or publicly. She was enthusiastic, Mahony was exultant, and the two struck up a friendship, with professional ramifications, that endured as long as they lived.

For the cause of children’s books to prosper, there needed to be someone to create the kinds of books that Mahony and Moore could wholeheartedly support — good new books to supplement the classics and substitute for the “trashy” series that Moore threw out of her libraries and Mahony refused to stock. On a visit to New York in 1919 Mahony called on Louise Seaman, the newly appointed children’s book editor at Macmillan, when she was still in makeshift quarters. Seaman, a constant traveler, lost no time in visiting the Bookshop. And another lifelong friendship was cemented.

In the children’s book community of New York, Moore and Seaman were bound to be thrown together, but they were not bound to be friends — Moore was considerably older, Seaman considerably more sophisticated. But Moore (b. Limerick, Maine, 1871), the nineteenth-century New England woman, liked nothing better than to take a taxi back and forth across New York’s new bridges, while Seaman (b. Brooklyn, New York, 1894), Vassar graduate and progressive-school teacher, was passionate about old books, ancient civilizations, and growing roses.

To these three partisans, children’s books were vehicles of imagination, and they promoted them in imaginative, enhancing ways — with sundry booklists and other printed ephemera, with a round of exhibits and programs and special events. But it was Mahony who had the most latitude, the greatest resources, and a knack for connecting books to life that amounted to a creative genius. Bookshop exhibits extended from historical French children’s books to child art; programs ranged from poetry afternoons for adolescents to lectures on educational psychology for adults. Among the booklists was a panoramic state-by-state listing of selected titles in the order of the states’ entry into the Union, entitled “All Aboard on the Old 44” and keyed to Hader illustrations for Cornelia Meigs’s Wonderful Locomotive, the “Old 44.” Traveling with books, in Mahony’s company, could take you almost anywhere.

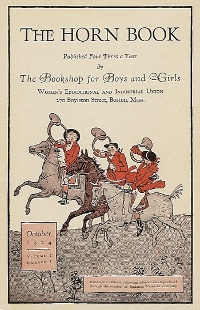

WITH THE HORN BOOK, she could go further. On a holiday in England in 1924, Mahony and Whitney decided to follow their promptings and start a magazine devoted entirely to children’s books. As an organ of the Bookshop, it would carry a Booklist, called just that, with brief notices of recommended new books. But it would be much more than a guide to good reading — a function Mahony and Whitney’s all-encompassing Realms of Gold soon came to perform. Rather, it would be an expression, and extension, of the Bookshop itself. A grander way, prospectively, to blow the horn for good books.

When the first issue appeared in October 1924, congratulations poured in. “I am so thrilled, excited, entranced, inspired . . . by the Horn Book that I want to send it to everyone I know,” wrote Louise Seaman, enclosing a check for eight subscriptions (at fifty cents each). Anne Carroll Moore carried around a copy and brandished it at meetings, to urge librarians to subscribe. Seaman had further reason to rejoice the following March on publication of her tribute to one of her authors, Padraic Colum, “Stories Out of the Youth of the World,” an article that Mahony had undoubtedly solicited. One hand washed the other, for decades. Mahony liked to have authors and illustrators write about themselves, and especially about the wellsprings of their work. She liked to have their editors, more than anyone else, write personality-pieces or overviews. That there might be a conflict of interest, that this might amount to unpaid advertising, never occurred to her. Everyone concerned had the same interest: the promotion of good books. And when the Horn Book produced its magnificent August 1928 issue celebrating Louise Seaman’s ten years at Macmillan, with articles on her authors and illustrators as well as on Seaman herself, Mahony was surprised and hurt at being criticized, by other publishers, for including fourteen pages from the current Macmillan catalog as a demonstration of the Seaman touch. They suspected her of being bought.

When the first issue appeared in October 1924, congratulations poured in. “I am so thrilled, excited, entranced, inspired . . . by the Horn Book that I want to send it to everyone I know,” wrote Louise Seaman, enclosing a check for eight subscriptions (at fifty cents each). Anne Carroll Moore carried around a copy and brandished it at meetings, to urge librarians to subscribe. Seaman had further reason to rejoice the following March on publication of her tribute to one of her authors, Padraic Colum, “Stories Out of the Youth of the World,” an article that Mahony had undoubtedly solicited. One hand washed the other, for decades. Mahony liked to have authors and illustrators write about themselves, and especially about the wellsprings of their work. She liked to have their editors, more than anyone else, write personality-pieces or overviews. That there might be a conflict of interest, that this might amount to unpaid advertising, never occurred to her. Everyone concerned had the same interest: the promotion of good books. And when the Horn Book produced its magnificent August 1928 issue celebrating Louise Seaman’s ten years at Macmillan, with articles on her authors and illustrators as well as on Seaman herself, Mahony was surprised and hurt at being criticized, by other publishers, for including fourteen pages from the current Macmillan catalog as a demonstration of the Seaman touch. They suspected her of being bought.

The Seaman issue came in at eighty-five substantial pages. In addition to the Macmillan material, there was a review of Bambi, still interesting today, by a well-known natural scientist; an article on the art of silhouette by John Bennett, whose new book, The Pigtail of Ah Lee Ben Loo, was illustrated with his silhouettes, and a companion-piece on Bennett’s inspired way with children by his editor Bertha Gunterman; a three-page send-off for Realms of Gold by its co-editor Elinor Whitney; and, in conclusion, a dozen pages surveying “Other Children’s Book Departments Since 1918,” their editors, and some of the books on each fall list. Coward-McCann was publishing Millions of Cats, and one of the “unusually interesting” illustrations is on the back cover.

THE MAGAZINE WAS METAMORPHOSING, slowly and then quickly, from an oversize bookshop newsletter into the all-but-official journal of “the new children’s book movement,” as Frederic Melcher called it. The subscription price doubled, to one dollar; the quarterly became a bimonthly, with ads. But the significant changes were internal. In 1932 Bertha Mahony married a wealthy furniture-manufacturer whose home was in Ashburnham, in central Massachusetts, beyond daily commuting range; she began to divide her time between Ashburnham and Boston. In 1934 she and Elinor Whitney resigned from the Bookshop to concentrate on the Horn Book, and it acquired its own good right-hand in the person of Beulah Folmsbee, an all-around professional who ran the office, handled subscriptions and advertising, designed the magazine, and got it out. In 1936 the Union, unable to replace Mahony and Whitney at the Bookshop, sold it into oblivion; Elinor Whitney married prep-school headmaster William Field, and withdrew from month-to-month operations; and Bertha Mahony Miller and Elinor Whitney Field, with their husbands and Horn Book printer Thomas Todd, assumed ownership of the magazine (upon William Miller’s putting its finances to rights).

To Anne Carroll Moore and other old Horn Book friends, this was a new beginning, both a casting off of fetters and an embarkation upon stormy seas. Moore was contributing advice, suggestions, admonishments, and articles right along; she put together an issue honoring Marie Shedlock, the fabled English storyteller, and wrote about Kenneth Grahame and other English personalities she’d known. In 1936, learning that the Horn Book was floating loose, she offered to donate to the cause — “if you think it would strengthen your subscription appeal” — a revived version of her old “Three Owls” column of critical commentary. At sixty-six, Moore was four years short of mandatory retirement, with its loss of entitlements; as a Horn Book fixture, she was sure to get review books and due respect. The magazine, in turn, got a splash of vinegar, a crusty voice.

Louise Seaman had meanwhile married corporate lawyer Edwin DeT. Bechtel; had sustained a horseback-riding injury that hadn’t healed properly; and in 1934 had resigned from Macmillan — all the better, it turned out, to learn about children and books. Especially young children and books. American picture books were in a state of infancy but growing faster than the ability to assess them soundly. The pictures were not traditional illustrations and not to be judged by traditional norms: Bertha Mahony Miller’s most aesthetic friend, Marguerite Mitchell, who had run the Bookshop gallery, could not see anything good in Marjorie Flack’s Angus books, for instance. Picture book texts were a new form of writing altogether.

Among the books by progressive educators that Louise Seaman Bechtel published at Macmillan were two unorthodox geographies by Lucy Sprague Mitchell of the Bank Street School, then called the Bureau of Educational Experiments. Much impressed with Mitchell’s work, Bechtel contributed to the second Here and Now storybook, Another Here and Now Story Book (1937) and took a special interest in the Writers Laboratory that Mitchell started, where Bechtel met and became friends with Margaret Wise Brown. The immediate consequence was an article on Mitchell by Brown and a Bank Street colleague run in tandem with a featured review of Another Here and Now Story Book by Bertha Miller — who admits to “doubting” the first book — in the May 1937 issue of the Horn Book. In effect, Horn Book star treatment for one of Anne Carroll Moore’s least favored people.

Bechtel herself wrote two keystone articles on the newest of the new, “Gertrude Stein for Children” and “Books Before Five.” She took on the comics, in 1941, when that was the hottest topic in children’s bookdom. She wrote major pieces about Elizabeth Coatsworth, Helen Sewell, Rachel Field, and others she’d worked with. When she went to Egypt, she discoursed on the year’s Egyptian books; when she delivered a paper, as she was often asked to do, it usually saw print in the Horn Book. She was a fluent, eloquent writer, vastly informed, and a balance to Moore in her outlook and tastes. But she was enough like Moore to write a lovely appreciation of Walter de la Mare — and Moore was enough like her to also like Gertrude Stein.

The person who stabilized the troika of Bechtel, Miller, and Moore was the Boston Public Library’s Alice Jordan, scholar of American children’s literature and a steady, persuasive reviewer. What she taught Bertha Miller about children’s books by special arrangement, she taught formally to Elinor Whitney Field and decades of Bookshop/Horn Book hands at the Simmons Library School. It was she who gave Miller her first public recognition, in the June 1929 Atlantic Monthly (the portrait on this issue’s cover appeared with that tribute); she who wrote the studies of nineteenth-century American writers that first appeared in the Horn Book in the early 1930s and eventually saw publication as From Rollo to Tom Sawyer (1948); she who touched off the Caroline M. Hewins Lectures, underwritten by Frederic Melcher, on historic New England writers and publishers, that the Horn Book, Inc., also published. And it was Jordan to whom Bertha Miller turned in 1939 to take over the Booklist when total responsibility for the magazine, along with personal concerns, overwhelmed her. For the next eleven years the Horn Book boasted short, substantive reviews — light enough for layfolk, knowledgeable enough for professionals.

Jordan and Bechtel and Moore also went on the masthead that year, along with Elinor Field, to shore up the Horn Book and its frazzled editor. This was no mere window dressing: the erstwhile colleagues became active collaborators, and Miller, to secure their advice and assistance, had to listen to Bechtel’s recital of her shortcomings and Moore’s reproaches for one dereliction or another (each endangering the future of children’s books). Pressures to change, pressures not to change.

Bechtel faulted her for New England insularity — and that, for Miller, was easy to correct. She entered into a correspondence with Gladys English, of the Los Angeles Public Library, to secure an article about Arna Bontemps and an article by him — both appeared in the January 1939 issue — and took up English’s suggestion that the Horn Book have a California issue timed to the forthcoming ALA Los Angeles conference. She started a new department, Hunters Fare, in which a librarian would answer readers’ (alleged) questions about books, and recruited Siri Andrews, then of the University of Washington, to take a turn conducting it. She invited Eulalie Steinmetz Ross, in charge of children’s work at Cincinnati, to speak frankly about Horn Book policies and practices — and Ross did. Andrews later became part of the Horn Book inner circle, and Ross became Miller’s biographer.

OVERALL, SHE HELD TO HER COURSE. And with Beulah Folmsbee to faithfully execute her projects, Alice Jordan to depend on for reviewing, and counselors near and far, she was poised for a decade of enormous productivity. It might be her last — she could not stave off retirement much longer. In the Horn Book she moved away from literature pure-and-simple and toward controversial subjects. Under the auspices of The Horn Book, Inc. — “our little close corporation” — she published the books that would keep her original vision alive and intact, notably Paul Hazard’s lyrical Books, Children and Men and the imposing volume widely known as “Mahony,” Illustrators of Children’s Books: 1744–1945. Both books had their roots in the Bookshop and exude its cultural aura. Serene and good-mannered, they seemed ageless a decade after their publication.

Miller worked devotedly on these books for many years — the same years she was reaching out to working librarians on the West Coast, in the Midwest and the South, and monitoring the news of the world for its relation to children. When she stepped down from the Horn Book editorship in 1951, she left it suspended between the timeless and the timely. And why not?

From the September/October 1999 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!