2018 School Spending Survey Report

To Inform and Delight: The Elements of Story — The Zena Sutherland Lecture

Salutations! I am honored to be here with all of you.

Salutations! I am honored to be here with all of you. I never met Zena Sutherland, but she’s been described as “short and feisty,” and I like short and feisty women, especially, as in Zena’s case, ones with passion and panache. When Zena was offered the job to become editor and sole reviewer for the Bulletin for the Center for Children’s Books, she had “no experience, but a lot of inclination.”

Salutations! I am honored to be here with all of you. I never met Zena Sutherland, but she’s been described as “short and feisty,” and I like short and feisty women, especially, as in Zena’s case, ones with passion and panache. When Zena was offered the job to become editor and sole reviewer for the Bulletin for the Center for Children’s Books, she had “no experience, but a lot of inclination.”Artists love that “flying by the seat of your pants” spirit. It’s an old aviation expression from when pilots flew planes with no navigational tools, relying instead on their judgment and intuition. Often my best art is made the same way, when I’m on the edge of what I’m capable of and beginning without knowing what the outcome will be.

My belief is that art comes from art. When we look at or experience art, we take away with us the elements that resonate, or show us the world in a new way. Looking at art as an artist is preparation for honing our own artistic style, or a way of interpreting the world. It’s a remix.

Tonight I’ll be answering the question: how did a scrappy little kid who’d rather be riding a bike and delivering doughnuts than reading fall in love with books? As well as how a painting, Milton Bradley, and collecting desiccated amphibians prepared me as a collage artist.

Growing up in Wyckoff, New Jersey, we were free-range kids living in a neighborhood filled with other whippersnappers and wisenheimers. I was the kid gluing macaroni to a paper plate and painting the assemblage. (Paper plates also make snazzy party hats.) We kids were left to our own devices to make our own fun and to negotiate getting along. We played stickball and kick-the-can, made

forts and lean-tos, and had the freedom to jump on our bicycles and scream around town, so long as we were back by dinnertime. Like E. B. White, we “spent [our] youth on bicycles and in trees.”

My brother had a paper route, and I wanted to make money, too, but girls weren’t allowed to have paper routes. (This was in the mid-1960s when girls couldn’t play Little League baseball or wear pants to school, either.) Never mind; I had a bicycle with baskets all ready to go, so I created a doughnut delivery route. On Saturday afternoons I went door-to-door to our neighbors, taking their doughnut orders. On Sunday mornings at the crack of dawn, and before the bakery got busy, I bought hot doughnuts and delivered them on my bicycle. From there, I began making and selling potholders, macramé plant hangers, and stained-glass ornaments. I was shameless, but I was in my element: I was an artist and an entrepreneur.

My brother had a paper route, and I wanted to make money, too, but girls weren’t allowed to have paper routes. (This was in the mid-1960s when girls couldn’t play Little League baseball or wear pants to school, either.) Never mind; I had a bicycle with baskets all ready to go, so I created a doughnut delivery route. On Saturday afternoons I went door-to-door to our neighbors, taking their doughnut orders. On Sunday mornings at the crack of dawn, and before the bakery got busy, I bought hot doughnuts and delivered them on my bicycle. From there, I began making and selling potholders, macramé plant hangers, and stained-glass ornaments. I was shameless, but I was in my element: I was an artist and an entrepreneur.If I wasn’t playing outside it was because I was too busy making paper dolls or playing with a Spirograph, an Etch A Sketch, some Paint-by-Numbers, or Colorforms. I was a persistent kid (I’m still a persistent kid), and these kits focused me; gave me structure; taught me about pattern, form, color, how to use tools and materials; and provided a kind of “guided play.”

I didn’t know it, but I was learning the way many artists have through the centuries. The early-nineteenth-century German educator Friedrich Froebel believed that children learned from activity and play. He created a “Play and Activity Institute,” introducing twenty activities, or “gifts,” as he called them, giving young children a way of learning through play with blocks, colored sticks, wooden mosaic tiles in geometric shapes, modeling clay, sewing, etc. Froebel later called his institute “Kindergarten,” or “child’s garden.” Because the “gifts” used basic shapes and forms, depicting nature was not representational but more abstract, finding the essence of the natural world and objects.

Froebel wrote, “From objects to pictures, from pictures to symbols, from symbols to ideas, leads to the ladder of knowledge.” Interestingly, a number of artists went to similar kindergartens: Paul Klee, Wassily Kandinsky, Buckminster Fuller of geodesic dome fame, Piet Mondrian, and others. The architect Frank Lloyd Wright was taught the Froebel method by his mother, and Wright later wrote, “The smooth shapely maple blocks with which to build, the sense of which never afterward leaves the fingers: so form became feeling.”

As kindergarten was being introduced to America, Milton Bradley, maker of toys and board games, went to a lecture about Froebel’s kindergarten. He was enthralled by the idea that very young children could learn through art and play and enrolled his two daughters. He was especially enamored with the trend to make kindergartens free, giving all young children the same start in life, almost like an early Head Start program. Bradley began manufacturing the Froebel gifts and went on to make crayons, colored paper, color wheels, flash cards, and watercolors. The toys I played with — Spirograph, Colorforms, even Tinkertoys and Erector sets — were all spin-offs of Friedrich Froebel, and of Milton Bradley.

As a child I read a bit, mostly comic books, and practically memorized the New Yorker book of cartoons. But I would rather make something than read. Some people have a book that defined their childhood. I have a painting.

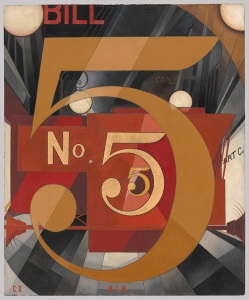

Charles Demuth's I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold

Charles Demuth's I Saw the Figure 5 in GoldWhen I was about seven years old, my Brownie troop went on a field trip to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City. My mom sent me off for the day with fifteen cents to buy a souvenir. I came home with a postcard of a painting by Charles Demuth, I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold. I loved the gigantic consecutive numeral fives, the reds and golds, the motion of a fire truck on a stormy night. It was exhilarating. I didn’t know that it was abstract art, or modern art, but I liked how it made me feel.

Not everything about growing up was as easy as selling doughnuts door-to-door. In school it seemed there were the kids who could draw and make art and the kids who were good at academics. I learned by doing, and by high school the academics barely held my attention. In order to reduce my academic load, my dad asked the principal to allow me to take shop and mechanical drawing at a time when girls weren’t allowed to take those classes (though, to be fair, boys couldn’t take home economics, either). Between those classes and art classes, I was able to get through high school with As and get into art school.

One of my roommates brought her favorite children’s books with her, including Else Holmelund Minarik’s Little Bear, illustrated by Maurice Sendak. She also brought books with illustrations by Arthur Rackham, Kay Nielsen, and others. Seeing them, I could imagine my own art in a children’s book. But I had no idea how to make a book or get it published or where to find out.

* * *

After art school, I moved to the Boston area, where there was a thriving book arts community. I took classes in calligraphy, paper-making, bookbinding, book construction, and design. I met artists who were making limited-edition, miniature, and one-of-a-kind books — a world I never knew existed. I began making and selling my own handmade books, all the while continuing to draw and paint.

The book as an object and art form became my focus. Every design decision in making a one-of-a-kind or artist’s book — the size of the book, type of papers used, hand lettering, binding construction — all focus to illuminate the story. Engineering these books from scratch gave me freedom to conceive a book as three-dimensional as I imagined. There was no better training for making children’s books.

While making my own books, I was creating an illustration portfolio; and to support myself I got a job at The Children’s Book Shop in Brookline, Massachusetts. The store had frequent author and illustrator signings with luminaries such as David Macaulay, Chris Van Allsburg, Lisbeth Zwerger, and others. Even my hero Maurice Sendak came to town to give a lecture. I bought all of their books to study and dissect, and after each event, when the crowds died down, I’d pepper them with questions about how they made their art, or what kind of paint they used, and how they got their first book published. Meanwhile, even though I was sending book dummies to publishers, they were all sent back politely declined. I thought if I could just get one book published, then I would know I had made it as an artist.

At about that time, illustrator Susan Jeffers gave me some great advice. She suggested that since so many children’s books have kids in them, I should learn to draw kids well, and put those pictures in my portfolio. I took her recommendation with a twist. I called twelve publishers in New York City, and made consecutive appointments to meet editors and art directors one month from that day. Then I gave myself the assignment to make a fresh new portfolio with twelve paintings based on Mother Goose rhymes, filled with kids of all ages and sizes. The self-imposed deadline was purposeful. It left no time for deliberating.

So the persistent, scrappy kid bought a navy blue suit and pink blouse, and looking, as one person remarked, like an airline steward, went to New York City and spent some anxious hours in publishers’ waiting rooms. To paraphrase Louis Pasteur, “Chance favors the prepared mind,” and at the end of that trip I came home with a contract for the forthcoming Pinky and Rex series by James Howe. It was a very lucky break to be paired with such an august author.

* * *

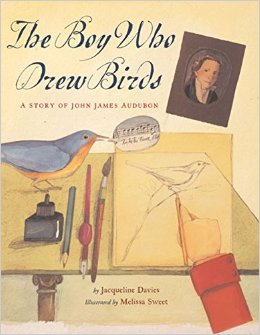

Those early books required a vivid imagination, but not much research. Then Ann Rider, who became my editor at Houghton Mifflin, asked me to illustrate The Boy Who Drew Birds: A Story of John James Audubon by Jacqueline Davies. As someone unfamiliar with picture-book biographies and who avoided nonfiction, this made me nervous. How could my whimsical style convey Audubon’s gorgeous realism? Studying Audubon’s art made me even more nervous. But intuitively I sensed that the book’s illustrations didn’t need to look like his art, they just needed to feel true to him.

Those early books required a vivid imagination, but not much research. Then Ann Rider, who became my editor at Houghton Mifflin, asked me to illustrate The Boy Who Drew Birds: A Story of John James Audubon by Jacqueline Davies. As someone unfamiliar with picture-book biographies and who avoided nonfiction, this made me nervous. How could my whimsical style convey Audubon’s gorgeous realism? Studying Audubon’s art made me even more nervous. But intuitively I sensed that the book’s illustrations didn’t need to look like his art, they just needed to feel true to him.The only thing to do was to travel to Mill Grove, Pennsylvania, where the story took place, and search for clues, hoping something would inspire the art. In Mill Grove I saw Audubon’s bedroom, where he wrote and drew; I saw his large, luscious prints from Birds of America and his taxidermy birds and mammals; and I saw his collections of feathers, eggs, and other bits of the natural world. I had collections like that too: nests, shells, and bones, and even a box of desiccated amphibians that were just like the eclectic collections Audubon had. These objects became the visual link to him, and this book taught me that even though collage is messy and chaotic, the layers and depth could convey more than paintings alone. Making art this way is slow and methodical, and, as with any art form, knowing what to leave out is as important as knowing what to put in.

Another bit of serendipity came while researching A River of Words: The Story of William Carlos Williams by Jen Bryant. I discovered that Williams’s poem “The Great Figure” was penned one rainy night as a fire truck screamed through the city. Now, remember the Demuth painting that I fell in love with when I was seven — I Saw the Figure 5 in Gold? It was this very poem by Williams that inspired Demuth to make that painting. Modernism had always been an inspiration to me, but this link brought it full circle.

I illustrated several more picture-book biographies: The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus by Jen Bryant and Balloons over Broadway: The True Story of the Puppeteer of Macy’s Parade (which I also wrote) about puppeteer Tony Sarg. While searching for my next book to write and illustrate, I thought: if I could write about anyone at all, who would it be? E. B. White — he was some writer! I had my idea and my book title.

I illustrated several more picture-book biographies: The Right Word: Roget and His Thesaurus by Jen Bryant and Balloons over Broadway: The True Story of the Puppeteer of Macy’s Parade (which I also wrote) about puppeteer Tony Sarg. While searching for my next book to write and illustrate, I thought: if I could write about anyone at all, who would it be? E. B. White — he was some writer! I had my idea and my book title.My strongest link to White’s writing was The Elements of Style by Strunk and White. I have seven editions of this book, between my house and studio. But who was I — not an avid reader, and a fairly novice writer — to make a book about one of America’s most beloved authors?

According to William Strunk Jr., the key to finding one’s style is by writing with sincerity, simplicity, and clarity, as well as by keeping in mind rule number thirteen from The Elements of Style (original edition), titled “Omit needless words”:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

Strunk's coauthor White later added, “There you have a short, valuable essay on the nature and beauty of brevity — sixty-three words that could change the world.”

Even as early as 19 BCE the poet Horace recognized the same when he said, “The aim of the poet is to inform or delight, or to combine together, in what he says, both pleasure and applicability to life. In instructing, be brief in what you say in order that your readers may grasp it quickly and retain it faithfully.”

With that in mind, this project still felt as if someone had placed an uncut diamond in my lap, so for the first year as I was sorting the content of the book I talked to no one about it but my editor.

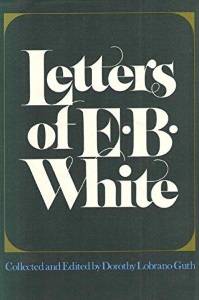

One of the first decisions I made about the project was regarding writing style. In reading the compiled Letters of E. B. White, what struck me was how accessible all his writing was. For those readers familiar only with his children’s books, I felt that including White’s other writings — his essays, letters, and poems — would give a window into his range of writings, and his own words would say more than I ever could. Instead of paraphrasing White’s work, I’d place him center stage, using quotes and passages from all his writings.

One of the first decisions I made about the project was regarding writing style. In reading the compiled Letters of E. B. White, what struck me was how accessible all his writing was. For those readers familiar only with his children’s books, I felt that including White’s other writings — his essays, letters, and poems — would give a window into his range of writings, and his own words would say more than I ever could. Instead of paraphrasing White’s work, I’d place him center stage, using quotes and passages from all his writings.Then, after I learned that he used a manual typewriter, the physical typewriter keys became part of the art, and in order to distinguish my text from his original words, his quotes were typed on a manual typewriter. With all these small and large elements, along with the archival materials, photos, and manuscript pages, the design of the book began to unfold.

About a year into the project, I wrote a letter to White’s granddaughter, Martha White, telling her about the book and asking how one goes about getting permission to use archival materials. I was naive in thinking that anyone can write a biography, and learned that permissions are not necessarily given just for the asking.

Martha met with me and saw the project underway. In the spirit of her grandfather, I gave her a goose egg with the innards blown out and attached a short quote (“I am sending you what I think is one of the most beautiful and miraculous things in the world — an egg”) from a letter he had once written to a group of sixth graders. Within a day or two Martha came over with White’s own scrapbook, home movies showing White shearing sheep, and a book he’d had since childhood. Some Writer! would not be the book it is without this material.

One thing that surprised me about White was that he was not, by his own account, a good reader. He said he was not a very literary fellow, except that he wrote for a living. White maintained that he wrote by ear for a party of one.

It was said of White that he never wrote a mean or careless sentence, and at his memorial service his stepson and fellow writer Roger Angell said:

White never wished his readers to think him deeper or wiser than he thought himself to be. Relieved of that frightful burden, he got more of himself onto paper in a lifetime than most writers come close to doing. Our knowledge of him seems wonderfully clear, like the view back down a series of steep meadows climbed on a cool day in autumn, and, looking back over that long path, one cannot imagine a leaf or a word that might have made it better.

White is, like his spider Charlotte, in a class by himself. He is also in a class of artistic innovators.

White is, like his spider Charlotte, in a class by himself. He is also in a class of artistic innovators.In his book Old Masters and Young Geniuses, David W. Galenson suggests there are two kinds of artistic innovators. One is conceptual, the other is experimental. Prodigies like Picasso tend to have a clear idea of where they want to go, and they execute it. Picasso said, “I can hardly understand the importance given to the word research,” and later wrote, “I never make trials or experiments.” Cézanne, on the other hand, was a painter for much of his life, but his success came later in his career. Late-bloomers are artists who are experimental; they work by trial and error, fermentation, incubation.

With all of the biographies I’ve worked on, I don’t believe any of the subjects were prodigies. Audubon, Sarg, Williams, Roget, White — all were the experimental type of artistic innovators. We know them from their great accomplishments, inventions, or contributions, but discovering their process is what makes them accessible and relevant, and entertaining to read about.

Making things is about discovery. Making things is a form of thinking. Drawing is thinking. Maybe Froebel and Milton Bradley were right: learning by play and activity puts kids on an even playing field. We take from art what we like, make a remix, and it becomes part of our own story. In the presence of art, we are not the same as we were before; the world is not as we thought it was. It’s more. I have seen it with my own eyes, flying by the seat of my pants.

From the September/October 2017 issue of The Horn Book Magazine. This article is adapted from the 2017 Zena Sutherland Lecture delivered on May 5, 2017, at the Harold Washington Library Center in Chicago.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

starr Kopper

Melissa, thanks for reminding us about the letter While wrote to the sixth grader and about the scrapbook and the materials Martha White brought you that made your book so multi layered.. "The medium is the message" - who said that? Always I think that the first pages of "Charlotte's Web" are a love song to the wonders of the barn.... all the smells and textures. And this is what you did for us with your book "Some Writer." I return to it again and again- just opening a spread- any spread. As I open any page of his letters and just start reading. I am sadly missing your workshop in Maine in May because of a conflict. I pray you will be so inspired by your participants that you will want to do another one. BEST WISHES, StarrPosted : Apr 25, 2019 10:38

starr Kopper

Melissa, thanks for reminding use about the letter While wrote to the sixth grader and about. the scrapbook and the materials Martha White b brought you that made your book so multi layered.. The medium is the message" - who said that? Always I think that the first pages of Charlotte's Web are a love song to the wonders of the barn.... all the smells and textures.and this is what you did for us with your book "Some Writer." I return to it again and again- just opening a spread- any spread. I am missing your workshop in Maine in May because of a conflict. I pray you will be so impaired by your participants that you will want to do another one. BEST WISHES, Starr KopperPosted : Apr 25, 2019 10:35