Jerry Spinelli Talks with Roger

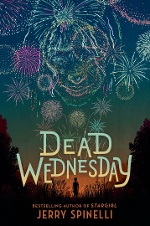

Newbery Medalist (and Boston Globe–Horn Book winner for the same book, Maniac Magee) Jerry Spinelli imagines what might happen to a boy on the day of his eighth-grade annual exercise in drunk-driving prevention, Dead Wednesday. Hint: he sees dead people.

Talks with Roger is a sponsored supplement to our free monthly e-newsletter, Notes from the Horn Book. To receive Notes, sign up here.

Sponsored by

Newbery Medalist (and Boston Globe–Horn Book winner for the same book, Maniac Magee) Jerry Spinelli imagines what might happen to a boy on the day of his eighth-grade annual exercise in drunk-driving prevention, Dead Wednesday. Hint: he sees dead people.

Roger Sutton: Is the idea of Dead Wednesday original or is it something that actually happens?

Jerry Spinelli: Oh, boy, you went straight to the right question. My answer is loaded with regrets, and you’re about to understand why. A fairly long time ago — I imagine it was about fifteen years — I got a letter from a teacher. This teacher was smart. This teacher had writers’ instincts. What she told me about was a day they had in their middle school every year. They call it Dead Wednesday — it’s one last shot at the kids who are going on to high school and will be lost to them forever, in the hands of whatever influences and temptations may come upon them in their high school years. Every eighth-grader is subjected to this. From the moment they enter school that day, they are considered to be dead. I believe they’re identified somehow as such; for example, they all wear black shirts or something.

Jerry Spinelli: Oh, boy, you went straight to the right question. My answer is loaded with regrets, and you’re about to understand why. A fairly long time ago — I imagine it was about fifteen years — I got a letter from a teacher. This teacher was smart. This teacher had writers’ instincts. What she told me about was a day they had in their middle school every year. They call it Dead Wednesday — it’s one last shot at the kids who are going on to high school and will be lost to them forever, in the hands of whatever influences and temptations may come upon them in their high school years. Every eighth-grader is subjected to this. From the moment they enter school that day, they are considered to be dead. I believe they’re identified somehow as such; for example, they all wear black shirts or something.

RS: As is in your book.

JS: Yes. Nobody pays attention to them. They’re ignored by students and by faculty. Nobody talks to them. Nobody sits next to them. They’re dead. The hope is that after such a day, they may be impressed enough to at least consider declining the oncoming temptations to drink and do drugs and drive recklessly and otherwise behave foolishly and so forth. An added feature, to help personalize this more and drive home the point that this is not just a game, not hypothetical: each of the “dead” eighth-graders is given a proxy, the name of a student of about the same age or high school age who died under circumstances that should never have happened, that was preventable if they had only used their head if they had only the right guidance. (Accidents don’t count.) Each of these eighth graders takes on the name and identity of another kid who died that year. Honestly, I don’t recall if I came up with that feature or if it was part of the letter.

RS: It’s funny what writers do with the things they learn, isn’t it?

JS: Yeah. Those are the basics of what I recall. It had been in my head for years, like a lot of things — I can be so slow. I finally woke up one day and said, “Oh my god, I’ve had this idea called Dead Wednesday sitting in my lap for fifteen years, and I haven’t done a thing about it. It’s about time.” I went looking for that letter, and I could not find it. This is where the regrets come in. When it came time to express my thank-yous in the beginning of the book, I could not name the teacher who started the whole thing, who gave me the idea. So I mention her, and that’s the best I can do. I can’t imagine myself throwing that letter away; my suspicion is it’s somewhere here, in the room I’m sitting in, which is my office. That letter is somewhere.

RS: Maybe it’s not real.

JS: Maybe it’s a muse, playing a trick on me. That would be lovely.

RS: The book doesn’t ever turn into a “Don’t drink and drive” book, though God knows in the 1970s we had plenty of those.

JS: Yes.

RS: But the book recognizes the spirit in which kids take such programs. It goes through their juvenile reaction to the tradition, and how they make something else of it than what was intended.

JS: Yes, exactly. Good point. I just took that basic situation — eighth-graders dead for a day in school, invisible — and asked myself, “Okay, what can I cook up to build around it?” And the result is a book called Dead Wednesday.

RS: It’s interesting to me that the book takes place over four disparate days, two of them together and two separate days later the same year, and it’s always in the present tense.

JS: I’ve used that method before — I like using it; it’s kind of fun. It’s my book, I can write it any way I want. When present tense feels right to me for a story, that’s how I do it. I can’t claim to be original in that. I remember how struck I was by how original it seemed, and how cool when I read — I believe it was Rabbit, Run by Updike in college.

RS: Where did you go?

JS: I went to Gettysburg College. That was one of the few unassigned books I read in those days. I was not a reader. Crazy that I’m a writer because I was not a reader.

RS: Your main character Robbie is not a reader either. Later in the book, I wondered if it was going to turn into, “Robbie becomes a reader.” But, again, that doesn’t happen either.

JS: Right.

RS: You had all the ingredients there. You have the authors living in little cottages, the log cabins, at his family’s retreat, and he has the opportunity to meet them. But he hates meeting them, and never becomes a reader, as far as we know.

JS: Right, as you said, at least not in the book. It ends on July 4. Reading is not first on his agenda, or mine, in his case. He’s got life to discover. That’s the focus. We can assume that sooner or later he’s going to get around to reading about life, but in the meantime, he’s got to be introduced to living it, and that’s what he does.

RS: I think my favorite line in the book is the one where Becca puts a daddy longlegs on his hand and he says it feels like “if atoms had feet."

JS: I remember writing that, yeah.

RS: But my second-favorite line is when Mean Monica tells Robbie to get a life, and he thinks: “I do have a life! You just can’t see it!” That will resonate with so many kids.

JS: I wasn’t thinking of it in that regard. I try not to think of the audience. But now that you mention it, I would like to think that’s true. From my point of view, for what it’s worth, I don’t even write for kids. As I look at it, I write about kids.

RS: Sure.

JS: If somebody came to me tomorrow from Random House and said, “We’re going to put out an adult edition of Dead Wednesday, so will you please go through it and make appropriate changes?” I wouldn’t change a thing. I don’t write for kids. I don’t write down to them. I write for the story. The way I like to say it — I sort of metaphorize it — I take my idea out for lunch and I ask it questions. “What makes you tick? How do you want me to write you?” And when the idea starts talking back to me, that’s when I get started. I’m writing for the story. I’m just writing the best story I can. I’m following the directions the idea’s giving me. I’m not writing it for those kids — but I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t aware of it. I’m happily, luckily aware that I have an audience, because forty years ago, I didn’t, and I would have given anything to have somebody come up and ask for my autograph. So when I say I don’t write for the audience, I don’t mean to be saying I take the audience for granted. Anything but. That’s why I write so that my stories might touch people so that they will reach readers. But it took so long to reach that point, I’m nothing but grateful that I finally arrived there.

RS: How much of you is Robbie, a.k.a. “Worm,” or is he you?

RS: How much of you is Robbie, a.k.a. “Worm,” or is he you?

JS: Parts of me are definitely Robbie. As a teenager, I had a case of acne that affected me profoundly, in ways that probably weren’t apparent to most other people. Unlike Worm, I was very definitely shy. But also unlike Worm — I have no idea, given how self-conscious I was about my face, how I overcame that — I became president of my class, valedictorian, three-sport participant, quarterback of the football team, most popular boy by vote, king of the prom, along with my girlfriend, who was queen. I had a high school experience for the ages — along with a face that I couldn’t face in the mirror. If anybody was paying close enough attention to me, which they undoubtedly were not, they would have noticed that I took great pains to never be in bright light, whether it was under fluorescent lights in the hallways, bordering the darker dance floor, or in the bright sunlight. I absolutely talk about that in the book; that was me.

RS: All this while, though, you were popular, a good student, got along with everybody. Maybe you were overcompensating.

JS: Who knows? It worked out well enough in both the short term and the long term, despite my private disquiet.

RS: One thing I think you got really well was the distinction between being an eighth-grader, who is our boy Worm; and Becca, his “ghost,” who was a junior in high school when she dies. You get the sort of older-woman crush he has on her, but there’s no real hint of romance between the two of them.

JS: I’m glad that’s what you got out of it because that’s what I intended. There’s certainly a crush aspect, no question, but it stops there. The extent to which there is any romance at all is confined to the last couple of pages.

RS: Right, with Mean Monica. And in the beginning, he has a crush on Bijou.

JS: Who he fancies throws him a smile on the bus. Then he comes back down to earth and winds up in fact falling for a girl who takes him by surprise.

RS: I love, though, that even that glance he misunderstood gives him such joy, if only for a few hours.

JS: Absolutely. Isn’t that what the life of a kid is? The first book I ever had published, in about 1982, was Space Station Seventh Grade, from Little, Brown. If you look at the table of contents, almost every chapter title is a single word. It’s kind of random. No real narrative arc to it. It’s sort of all over the place. That’s intentional. My point there is that a kid’s life happens in fragments in a lot of ways. It doesn’t have a coherence that we force upon ourselves when we grow up and identify ourselves and then cling to that identity, lest we feel lost at sea. But a kid hasn’t gotten the hang of that yet, nor do they feel the need to strap themselves into an identity. So their life takes place in fragments, unrelated, non-sequiturs all over the place. My editor didn’t seem to appreciate that, at least not insofar as I expressed that idea by the suggested title “Stuff,” which was meant to reflect the kid’s life. My editor gave it the title Space Station Seventh Grade.

RS: So how does a writer for children, going beyond the discussion we just had before about you not writing for children — how do you negotiate, for example, when you think back on your complexion problems and you think the whole world is looking at you, however many years it is later — probably fifty years, right? — and you realize: no one was really paying me that attention. How do you convey the experience of childhood with the benefit of hindsight as an adult without making it from an adult’s perspective?

JS: You remember, Roger. I’m often asked — any author is asked — where you get your ideas from. I have a standard answer: everyday life, imagination, and memory. In terms of memory, I just saw a Winnie-the-Pooh quote recently. He’s there with his buddy Christopher Robin, and he says, “We didn’t realize we were making memories, we just knew we were having fun.” That’s what I was doing without knowing it in the years when all I wanted to be was a Major League shortstop. I had no aspirations of being a writer. I didn’t even read. But I was creating memories, and they were staying with me, for whatever reason. The very first public talk I gave was in Indiana, Pennsylvania, home of Jimmy Stewart, at the university there. It was on the occasion of the publication of my second book, Who Put That Hair in My Toothbrush? I gave my little talk, and then there was a Q&A afterward, and some guy — I remember him being toward the front, over to the left — he raised his hand and said, “How do you remember all this stuff?” That was a revelation to me. Until that guy raised the question, it had never occurred to me that everybody didn’t remember all that stuff. I thought it was like breathing. I didn’t really have an answer; I just made a joke of it, said: “Well, I guess I never grew up.” And I guess there’s part of me that never did. I’m not big on overanalyzing things, especially the good stuff. In many cases, it’s not so much the incident, or the string of fragmentary episodes that comprised my kid-hood, but how I felt about them, how they affected me, that has remained in my memory more tenaciously than the incidents themselves. That’s as far as I can go. As I said, I thought everybody remembers all that stuff. When I wrote Space Station Seventh Grade, I was writing about a thirteen-year-old kid. I had already written four failed novels over fifteen years. This was number five. To the extent that I could even fantasize about a reading audience, I imagined adults. I had no idea there was such a thing as kids’ books. I had left that behind with Dick and Jane in first grade. I just wrote it out, assuming that if I was lucky enough to actually get this thing published, I imagined people like you and me, who would find it interesting, if not entertaining, and probably funny, to look back on those days. I’ve always enjoyed looking back on those days. Maybe that’s the key to your question. I certainly like to think I don’t live in the past. I can’t, not with six kids, twenty-three grandkids, sixteen great-grandkids. They keep me in the present.

RS: I wonder if remembering the feelings about things more than the actual things themselves is the key to what allows you to turn those feelings into stories.

JS: I wouldn’t be surprised.

RS: Because you’ve detached yourself already from the actual details of the memory, so you can apply the feelings to an entirely new character and situation.

JS: Absolutely. Being the writer, the one who is creating this story, I’m free to attach those feelings to whatever I decide to cook up.

Sponsored by

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!