What Makes a Good Sports Novel?

“Mike backed up at the ping of the ball against the metal bat, sensing a long, high fly.

“Mike backed up at the ping of the ball against the metal bat, sensing a long, high fly. He felt a flush of joy. He was exactly where he wanted to be, in the center of the universe, racing a baseball, sure he was going to win.”

“Mike backed up at the ping of the ball against the metal bat, sensing a long, high fly. He felt a flush of joy. He was exactly where he wanted to be, in the center of the universe, racing a baseball, sure he was going to win.”Robert Lipsyte’s recent novel Center Field starts with the above paragraph, and this is where all good sports novels start — with the game. It’s what attracts the reader, what makes a sports novel different from other novels. Lipsyte’s book opens with several paragraphs about high school student Mike Semak playing center field, beautifully describing Mike’s love of the game, offering a sense of what sports should be all about, what the game can be and should be.

Sports books for young adults are about much more, however, and it soon becomes apparent that Lipsyte is not writing an ode to high school sports. A new player joins the team (a competitor for Mike’s position perhaps), ethnic slurs begin, and Lipsyte takes readers right into the heart of what he calls “jock culture,” where racism, homophobia, bullies, steroids, sexism, and overzealous coaches, businessmen, and parents eat athletes alive. Teen readers are looking for honest novels with mature content and flawed heroes who must find a moral high road, novels that take them seriously as young adults and reflect the world as they are beginning to experience it. Sports novels such as Center Field, Carl Deuker’s Gym Candy, Fredrick McKissack Jr.’s Shooting Star, and Chris Crutcher’s Whale Talk, among many others, deliver the goods.

Sports books for young adults are about much more, however, and it soon becomes apparent that Lipsyte is not writing an ode to high school sports. A new player joins the team (a competitor for Mike’s position perhaps), ethnic slurs begin, and Lipsyte takes readers right into the heart of what he calls “jock culture,” where racism, homophobia, bullies, steroids, sexism, and overzealous coaches, businessmen, and parents eat athletes alive. Teen readers are looking for honest novels with mature content and flawed heroes who must find a moral high road, novels that take them seriously as young adults and reflect the world as they are beginning to experience it. Sports novels such as Center Field, Carl Deuker’s Gym Candy, Fredrick McKissack Jr.’s Shooting Star, and Chris Crutcher’s Whale Talk, among many others, deliver the goods. Lipsyte won the 2001 Margaret A. Edwards Award for books that “transformed the sports novel to authentic literature with their gritty depiction of the boxing world.” Lipsyte’s ground-breaking The Contender, written over forty years ago, and similar novels such as Bruce Brooks’s The Moves Make the Man and Walter Dean Myers’s Game, are less intensely sociological in analyzing jock culture and more about the life lessons a sport can impart. Older middle school students love these novels for their solid sports action and for their depictions of likable protagonists who learn life lessons from the sports they love. Alfred Brooks in The Contender comes to understand that “everybody wants to be a champion…Nothing’s promised you…You have to start by wanting to be a contender.” In Game, Drew Lawson, like Alfred Brooks, knows the lure of the streets, where people fall behind on their game and lose interest in the score. But he says, “I was about ball. Ball made me different than guys who ended up on the sidewalk framed by some yellow tape.” This is a novel always popular with my eighth graders for the basketball game sequences (by a writer who knows the game), the portrait of the personable main character, and Drew’s struggle to stay true to his dreams.

Lipsyte won the 2001 Margaret A. Edwards Award for books that “transformed the sports novel to authentic literature with their gritty depiction of the boxing world.” Lipsyte’s ground-breaking The Contender, written over forty years ago, and similar novels such as Bruce Brooks’s The Moves Make the Man and Walter Dean Myers’s Game, are less intensely sociological in analyzing jock culture and more about the life lessons a sport can impart. Older middle school students love these novels for their solid sports action and for their depictions of likable protagonists who learn life lessons from the sports they love. Alfred Brooks in The Contender comes to understand that “everybody wants to be a champion…Nothing’s promised you…You have to start by wanting to be a contender.” In Game, Drew Lawson, like Alfred Brooks, knows the lure of the streets, where people fall behind on their game and lose interest in the score. But he says, “I was about ball. Ball made me different than guys who ended up on the sidewalk framed by some yellow tape.” This is a novel always popular with my eighth graders for the basketball game sequences (by a writer who knows the game), the portrait of the personable main character, and Drew’s struggle to stay true to his dreams. But sports books don’t always have to ask the Big Questions; sometimes little insights and gentle revelations are what matter most in a story. In Mick Cochrane’s achingly beautiful The Girl Who Threw Butterflies, eighth-grader Molly Williams makes the baseball team on the strength of the knuckleball her father taught her before he was killed in a car crash. Funny how a pitch can make a reader cry — this little miracle of a pitch with its butterfly dance, the pitch with a sense of humor and a bit of mischief, the pitch that connects Molly with her father and helps her to let him go. Along the way she learns the lessons sports are always able to offer about teamwork, grit, and courage, and the possibility of failure and loss but going on anyway. There are no big flashing signs announcing Big Questions answered here, just a young girl making her way through middle school, knowing there’s more to come in her life, like a baseball scorebook with the “blank squares in the inning, waiting to be filled in.”

But sports books don’t always have to ask the Big Questions; sometimes little insights and gentle revelations are what matter most in a story. In Mick Cochrane’s achingly beautiful The Girl Who Threw Butterflies, eighth-grader Molly Williams makes the baseball team on the strength of the knuckleball her father taught her before he was killed in a car crash. Funny how a pitch can make a reader cry — this little miracle of a pitch with its butterfly dance, the pitch with a sense of humor and a bit of mischief, the pitch that connects Molly with her father and helps her to let him go. Along the way she learns the lessons sports are always able to offer about teamwork, grit, and courage, and the possibility of failure and loss but going on anyway. There are no big flashing signs announcing Big Questions answered here, just a young girl making her way through middle school, knowing there’s more to come in her life, like a baseball scorebook with the “blank squares in the inning, waiting to be filled in.”Often, what middle school readers like most is the vicarious thrill of being at the big event, rubbing shoulders with celebrities, or simply being involved in a game they know well. When my seventh graders grab for the newest novel by John Feinstein or Mike Lupica, they’re not looking for analyses of jock culture, sports metaphors, and lessons about life. They love Feinstein’s tantalizing mysteries about the Final Four, the Super Bowl, the World Series, and the U.S. Open tennis tournament. Add young reporters Stevie Thomas and Susan Carol Anderson, who must follow leads and figure things out, and you have the makings of a fine series that has attracted legions of fans.

Middle school students love Lupica’s sports stories, which seem like pages right out of their own sports lives — playing Little League, playing on the big field for the first time, going to sports camp, being on a travel team. Lupica’s Miracle on 49th Street is the title that most appeals to girls in my seventh- and eighth-grade classes, since the protagonist is a twelve-year-old girl who believes that Josh Cameron, star of the Boston Celtics, is her father and sets out to prove it to him. It’s a story of a feisty girl, a self-absorbed athlete, and the relationship that just might come true between them.

Middle school students love Lupica’s sports stories, which seem like pages right out of their own sports lives — playing Little League, playing on the big field for the first time, going to sports camp, being on a travel team. Lupica’s Miracle on 49th Street is the title that most appeals to girls in my seventh- and eighth-grade classes, since the protagonist is a twelve-year-old girl who believes that Josh Cameron, star of the Boston Celtics, is her father and sets out to prove it to him. It’s a story of a feisty girl, a self-absorbed athlete, and the relationship that just might come true between them.And what could be better than Lupica’s Heat? It’s set next door to Yankee Stadium — “just down the street, and a world away”; the protagonist, Michael Arroyo, says he’s twelve years old, but his throwing arm borders on the magical and seems too good to be true; and readers even get to meet a celebrity, famous Yankee pitcher El Grande. It’s a beautifully written tale with heart, when even heroes become friends, and ghosts of fathers look on in Yankee Stadium, and at least for one glorious moment all is right with the world.

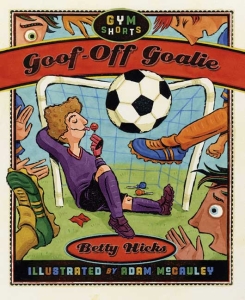

Sports novels for the youngest readers work best when they even more closely mirror the age, lives, and interests of their fans. They usually have to be about a sport the reader actually plays or is going to try out for, involve a hobby the reader has, or incorporate a mystery or an adventure. The Gym Shorts series by Betty Hicks is popular with second- and third graders. Swimming with Sharks and Goof-Off Goalie, for example, have kid appeal: attractive covers (illustrated by Adam McCauley), plenty of humor, sports that kids of this age often try, humorous and frustrating situations kids can relate to, and simple prose full of action. Dan Gutman’s Honus & Me has young Joe Stoshack finding a rare and valuable Honus Wagner baseball card, traveling in time, and being coached by the star himself, helping Joe’s game go from pitiful to great. That provides quite a wow factor for young readers, inducing that jaw-dropping sense of wonder, which is what sports and books about sports can embody.

Sports novels for the youngest readers work best when they even more closely mirror the age, lives, and interests of their fans. They usually have to be about a sport the reader actually plays or is going to try out for, involve a hobby the reader has, or incorporate a mystery or an adventure. The Gym Shorts series by Betty Hicks is popular with second- and third graders. Swimming with Sharks and Goof-Off Goalie, for example, have kid appeal: attractive covers (illustrated by Adam McCauley), plenty of humor, sports that kids of this age often try, humorous and frustrating situations kids can relate to, and simple prose full of action. Dan Gutman’s Honus & Me has young Joe Stoshack finding a rare and valuable Honus Wagner baseball card, traveling in time, and being coached by the star himself, helping Joe’s game go from pitiful to great. That provides quite a wow factor for young readers, inducing that jaw-dropping sense of wonder, which is what sports and books about sports can embody.H

ow much sports does a book have to contain in order to be a sports novel? Is Virginia Euwer Wolff’s Bat 6 a sports novel? Deborah Wiles’s The Aurora County All-Stars? Edward Bloor’s Tangerine? I would say yes on all counts. In each, a sport is employed to reveal a character, develop a conflict, or advance a plot, even if the books aren’t just about sports. When I think of the various lists put together by librarians on books of various themes, or the books on children’s literature with chapters devoted to various genres, these books, and many books like them, should be on the sports lists, but on other lists, too — by time period, locale, and other themes. Few sports novels are only about sports; if they’re any good, they’re about lots of things in life — family, friends, the street, jock culture, and the like. Sports novels that don’t end up on these lists often miss the boat: too much melodrama, not enough play-by-play; nonstop action but weak characterization; or sports lingo misused, revealing a writer who doesn’t really know the game.

ow much sports does a book have to contain in order to be a sports novel? Is Virginia Euwer Wolff’s Bat 6 a sports novel? Deborah Wiles’s The Aurora County All-Stars? Edward Bloor’s Tangerine? I would say yes on all counts. In each, a sport is employed to reveal a character, develop a conflict, or advance a plot, even if the books aren’t just about sports. When I think of the various lists put together by librarians on books of various themes, or the books on children’s literature with chapters devoted to various genres, these books, and many books like them, should be on the sports lists, but on other lists, too — by time period, locale, and other themes. Few sports novels are only about sports; if they’re any good, they’re about lots of things in life — family, friends, the street, jock culture, and the like. Sports novels that don’t end up on these lists often miss the boat: too much melodrama, not enough play-by-play; nonstop action but weak characterization; or sports lingo misused, revealing a writer who doesn’t really know the game.As an English teacher and writer, I always notice the writer’s prose style. The best sports writing — for adults and for young readers — has always been lean and muscular, with an emphasis on active verbs and concrete nouns and spare sentences that dance, a style perhaps the truest heir of Hemingway’s revolution in prose style in the twentieth century. Much of the best sports writing for adults appears in the sports columns of newspapers across the country, and some of the best sports novelists for young readers bring their experience as newspaper columnists to the world of children’s literature, writers such as Mike Lupica, John Feinstein, and Robert Lipsyte. In an interview with Book Links magazine, Lipsyte said he hoped his writing had improved in the forty years since The Contender: “I’d like to think I’m a better writer today so the sentences would dance more.” That’s something I look for and that kids notice, at least intuitively, when they read. A plodding, verbose style doesn’t cut it for a sports novel.

Rich Wallace’s debut novel, Wrestling Sturbridge, is notable for its prose style: spare, matter-of-fact short sentences full of specific details — nothing florid — and lively verbs accumulate into a rock-solid portrait of small-town Pennsylvania and a 135-pound wrestler who’s second-best on the team but wants to be state champion. Stellar prose style can come from Lipsyte’s “dance” of descriptive sentences or Wallace’s understated style and use of dialogue to show character or John H. Ritter’s mastery of voice in The Boy Who Saved Baseball, which lures readers in with a narrative tall-tale voice evoking the mythic quality of baseball and foreshadows the heroics to come, akin to W. P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe, the basis for the movie Field of Dreams.

Rich Wallace’s debut novel, Wrestling Sturbridge, is notable for its prose style: spare, matter-of-fact short sentences full of specific details — nothing florid — and lively verbs accumulate into a rock-solid portrait of small-town Pennsylvania and a 135-pound wrestler who’s second-best on the team but wants to be state champion. Stellar prose style can come from Lipsyte’s “dance” of descriptive sentences or Wallace’s understated style and use of dialogue to show character or John H. Ritter’s mastery of voice in The Boy Who Saved Baseball, which lures readers in with a narrative tall-tale voice evoking the mythic quality of baseball and foreshadows the heroics to come, akin to W. P. Kinsella’s Shoeless Joe, the basis for the movie Field of Dreams.For an old English teacher trying to teach children in an electronic age, excellent sports writing can demonstrate the power of story, the power of good writing on subjects kids care about. Sports writer Dan Jenkins once told Mike Lupica, when Lupica was beginning to work in television, not to give up his sports column. Jenkins said, “They respect you if you write. The dumber the world gets, the more the words matter.” That’s what we want for young readers — stories by writers who care enough to make the words matter.

Good Sports

Tangerine (Harcourt Brace) by Edward Bloor

The Moves Make the Man (Harper & Row) by Bruce Brooks

The Girl Who Threw Butterflies (Knopf) by Mick Cochrane

Whale Talk (Greenwillow) by Chris Crutcher

Gym Candy (Houghton) by Carl Deuker

Cover-Up: Mystery at the Super Bowl (Knopf) by John Feinstein

Honus & Me: A Baseball Card Adventure (HarperCollins) by Dan Gutman

Goof-Off Goalie (Roaring Brook) by Betty Hicks; illus. by Adam McCauley

Swimming with Sharks (Roaring Brook) by Betty Hicks; illus. by Adam McCauley

Center Field (HarperTeen/HarperCollins) by Robert Lipsyte

The Contender (HarperCollins) by Robert Lipsyte

Raiders Night (HarperTeen/HarperCollins) by Robert Lipsyte

Heat (Philomel/Penguin) by Mike Lupica

Miracle on 49th Street (Philomel/Penguin) by Mike Lupica

Shooting Star (Atheneum) by Fredrick McKissack Jr.

Game (HarperTeen/HarperCollins) by Walter Dean Myers

The Boy Who Saved Baseball (Philomel/Penguin) by John H. Ritter

Wrestling Sturbridge (Knopf) by Rich Wallace

The Aurora County All-Stars (Harcourt) by Deborah Wiles

Bat 6 (Scholastic) by Virginia Euwer Wolff

From the January/February 2011 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!