Eric Carpenter takes readers into the mind of a (hypothetical) Caldecott committee member determined to convince his fellow committtee members to vote for the amazing Nina, illustrated by Christian Robinson.

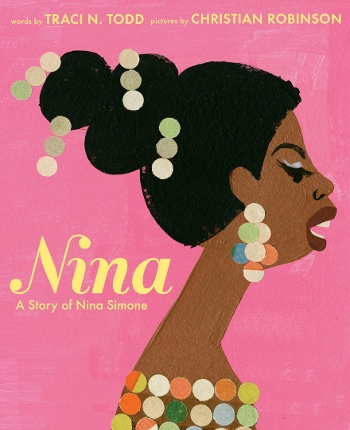

Instead of spending time talking about why I love Nina: A Story of Nina Simone, written by Traci N. Todd and illustrated by Christian Robinson, this Calling Caldecott blog post is my attempt to take readers into the mind of a committee member — the strategizing, the planning, and how one might present a title to their committee during the January gathering. I am not claiming that all award committee members take this approach to their work, but if I were on an award committee and charged with introducing a book of this magnitude, this is how I would go about ensuring a shiny seal is placed on the book by Saturday night.

Instead of spending time talking about why I love Nina: A Story of Nina Simone, written by Traci N. Todd and illustrated by Christian Robinson, this Calling Caldecott blog post is my attempt to take readers into the mind of a committee member — the strategizing, the planning, and how one might present a title to their committee during the January gathering. I am not claiming that all award committee members take this approach to their work, but if I were on an award committee and charged with introducing a book of this magnitude, this is how I would go about ensuring a shiny seal is placed on the book by Saturday night.

The elephant in the room:

Two excellent books in one year by the same illustrator (Robinson also illustrated Milo Imagines the World) might create a difficult situation. The Caldecott manual does not define the phrase "individually distinct," which allows each committee to come to a collective consensus on the definition of this important term. If I were at the Caldecott table, I would want to make sure everyone on the committee agreed on the meaning and implications of this important element of the definition of "distinguished."

The dictionary definition of distinct is ”distinguishable to the eye or mind as being discrete or not the same.” This definition does not help us here, as no two picture books of a given year are truly indistinguishable from each other. In this context, the term individually distinct would seem redundant. Instead, the manual must be leading us to define individually distinct as it relates to the criteria.

Is the picture book under consideration individually distinct in its execution of the artistic technique employed? Quoting from the copyright page of Nina, we see that Robinson employed “acrylic paint, collage, and a bit of digital manipulation.” If Robinson’s other 2021 title (Milo) is on the table — and I’m sure it is — we would see that the same exact statement is included on the copyright page. Does that mean neither book is “individually distinct in its execution of the artistic technique employed"? This is a question the committee must answer. I believe if you focus on the execution of the techniques, we would find that Robinson’s execution is unique in both titles, despite the similarity of medium. Furthermore, it is not simply how Robinson executes his art but how this art makes meaning for the reader. I would contend that what differentiates the two Robinson titles, and elevates Nina, is the purpose or reason behind the technique’s use to further the themes and story. Whereas, in the case of Milo, Robinson seems to be, in many instances, simply showing the reader what is described in the text, in Nina Robinson is complementing the text by allowing the artwork to add layers of meaning and tone and to impart information to the reader that is not conveyed in the text. To put this in terms of the criteria, as one must around the Caldecott table, the artwork in Nina delineates the plot, theme, characters, setting, mood, and information in a manner that is distinct from Robinson’s work in Milo.

With this argument addressed, the next step would be to convince the committee that Nina is more distinct than not just Milo but all other titles under consideration.

The strategy:

The goal is simple: to persuade at least half of the people around the table to write the word Nina on the top line of their ballot on Saturday evening. Each member can vote for only three titles. Remember that each member nominated seven titles to the committee in the months leading up to the meeting. All members will be giving up at least four of the titles they nominated — titles they have already painstakingly whittled down from the hundreds of books they read in that year and the dozens they truly loved. In all probability, some or even most of the members didn’t nominate Nina, so I would be doing everything I can to persuade at least seven members to believe in the distinguished nature of this book so much that they place it in their top three. To do this we must show how Nina is distinguished in a multitude of ways and is more distinguished than any of the titles my fellow committee members currently find most distinguished.

To do so I will speak persuasively about the book’s distinctive elements only in terms of the criteria — not personal experiences; not how the story, themes, or concepts make me feel emotionally; and not the importance of the story/subject. I will speak about how the artwork delineates the plot, themes, characters, setting, mood, and the information delivered through the book. I will also talk about how the book’s artwork recognizes its young audience and rewards their patience and illuminates its subject in a manner that the child reader can comprehend. I will show how Robinson’s stylistic choices are appropriate for the book's themes and story. This persuasive argument would occur over multiple days. The foundation for this argument would have been presented to the committee when I nominated the title during the fall. The hope is that other committee members read the reasons stated for Nina’s nomination and reviewed the book with these points in mind.

Once the committee meeting begins, you listen to all your brilliant fellow committee members speak to the wonderful artwork and visual storytelling techniques found in the dozens of nominated titles. You take notes and add your own opinion to the discussion, but never far from your mind is how these fourteen other individuals might be voting when balloting begins and how they view Nina (and whom you must persuade). You notice which criteria are most often discussed and which are least emphasized. You consider points of comparison with aspects of titles that seem to have plenty of support so that you can compare these titles with Nina and, ideally, show how Nina does these things in an even more distinguished way. And while you are doing all of this, you also have an open mind and are willing to be persuaded by your peers. You never know: Maybe there’s a title you overlooked that may rise to the top in a day’s time.

While you take in all this information, you have your own planned presentation, the one that will introduce the discussion of Nina. You’ve probably looked over your notes many times — perhaps on the plane and certainly during breaks — and you’ve made changes as you have seen and heard the discussion of other titles. The text below is what I would want to convey to my fellow committee members when discussing Nina for the first time, leading with the book’s foremost strengths — in this case, how Robinon’s art delineates theme, mood, and character.

The argument:

In any story of Nina Simone one would not be surprised to see the piano take prominence (center stage, if you will). Including on the cover, case cover, and endpapers, Robinson shows the readers a piano or keyboard twenty-six times. This level of repetition clearly deserves a closer look. Reading through Nina with careful attention to the pianos is a great example of the way Robinson visually delineates the mood, themes, characters, and information — from the small upright piano in Nina’s (who is then Eunice) North Carolina home to the grand pianos she first encounters in the white homes of Mrs. Miller and later Miss Mazzy. These instruments show readers the vast differences between Black and white families in the South. These differences are clear to even the youngest readers — such as the spread where we see David being separated from young Eunice (large hand-lettering on the background stating “White Only” and “Colored Only”), while the children lock eyes and their mothers, employer and employee, look away. The text states: “There was nothing to be done.”

The contrast in piano forms is repeated later in the narrative. Nina sits at a large grand piano for her audition at the Curtis Institute, and this is juxtaposed with the blue upright in the New Jersey dive bar where Nina finds employment after the Curtis Institute turns her away. The next time Nina is shown playing a grand piano, she is shown on a television screen in the spread that depicts her rise to fame, the accompanying text ending with “Ms. Simone had arrived!”

The reader assumes the narrative will continue on this high note and will depict more examples of Nina’s popularity or triumphs, but instead, as we turn from the television screen spread, we encounter what I consider to be the most dramatically striking spread of 2021. Two thirds of the verso is the midnight black of a raised grand piano lid. Inside the piano, Robinson has depicted scenes of protest and police brutality — images that immediately connote the deep-South protests of the early 1960s. On the piano bench on the lower portion of the recto lies Nina, asleep. She is exhausted. The text asks, “How could she join a movement when she could hardly move?” This image is why the Caldecott Award exists. It is why, when we consider the criteria, we look at how the art delineates the themes, the characters, the mood, the setting, and the information through pictures. This single spread, this portrait of exhaustion, is a perfect example of this crucial piece of the criteria. It is exhaustion from the hard work of an individual rising to the top of the musical world, but also exhaustion caused by the constant toll of racism. It is exhaustion caused by the White supremacist patriarchy violently fighting against any attempt at progress. Robinson captures all of this exhaustion in a single image— Nina asleep while the world around her begins to burn. It's a mood the reader instantly understands despite — and because of — our expectations just before turning the page. We the reader expected to see Nina triumph; she had, after all, finally "arrived." Instead, we see that success is its own struggle, especially when the success occurs in a world where hatred and bigotry dominate.

The pages that follow are a visual feast. First, in the spread immediately following the one described above, Robinson shrinks both Nina and her massive, stage-spanning grand piano. In an exceptional use of scale, Robinson places Nina and a grand piano on the stage of Carnegie Hall, the apex of any musician’s career. The piano is massive in relation to the stage, but both Nina and her instrument are dwarfed by the size of the hall and its audience. The brilliant red seats, carpet, and many balconies overwhelm Nina during her performance. The text assures us that the concert was a triumph. We are not surprised that the mostly white crowd was "clapping, cheering, shouting for more." The visuals of this spread also prepare us for the final bit of text: “Except …” Robinson’s use of scale and color lets the reader know that Nina’s concert can’t simply be a celebration.

What follows is another viscerally stunning spread that explains the “except ...." We discover that on the same day of the Carnegie Hall concert, Martin Luther King Jr. was arrested in Birmingham, Alabama. Here, Robinson has pushed Nina almost entirely off the page. At the extreme right she sits at her piano, half her face and body cut off by the edge of the page. Inside her piano, Robinson shows King and some of his fellow protestors behind iron bars. The verso features yellow and orange flames cut from a text — if I were on the actual committee, I would be spending a lot of time trying to figure out if the torn paper is the text from King’s "Letter from Birmingham Jail” — and gray smoke rises from the fire of the civil rights movement. It is also here, for the first time, that Nina is shown with a microphone, one that has the power to amplify not only her singing voice, but her voice as an advocate for change.

More equally powerful spreads follow — such as a depiction of Nina at a large grand piano filled this time with the 16th Street Baptist Church, gray smoke and those same orange and yellow flames rising from this holy building. Nina plays for Addie, Cynthia, Carole, and Carol, who sit or stand beside Nina’s bench. On the next spread, the fire motif continues. This time red torn paper joins the orange and yellow, bringing more heat to the fire as Nina, at the piano with a tight afro and slacks, is joined by a band while the text tells us what we can clearly see: “Nina was done being polite.”

A rare pianoless spread comes next. On the recto, Nina is on her feet, microphone in hand, in front of a group of marchers demanding dignity. On the verso, Robinson depicts a lunch counter sit-in, cleverly displaying the counter and protestors in profile in a way that visually rhymes with a pianist at her piano.

The book’s largest piano is next. The lid contains the eternity of the Lincoln Memorial, the reflecting pool, and the Washington Monument. The text refers to both the white backlash in response to Nina's activism as well as the death of Martin Luther King Jr. Nina, chin up, is shown at the keys, steadfast against the hatred directed toward her and prepared to take on the grief of a nation as she asks in song, “What will happen, now that the King of Love is dead?” This — the most static spread of the book, with its massive piano and sturdy Nina surrounded on all sides by empty white space — gives the reader a chance to catch their breath and reflect on the gravity of the preceding pages. Here, we digest the transformation we’ve witnessed: the exhausted Nina asleep on her piano’s bench after finally “arriving” is now the powerful voice of a nation — singing, leading, and fighting for change. We can almost feel the weight on Nina’s shoulders. Here, again, the artwork does the heavy lifting, conveying mood and themes.

And, finally, the last spread before the backmatter depicts Nina in a black dress, standing up from the piano bench, the angle of her back perfectly matching the angle of the raised lid. She's a solitary musician with her instrument. In its straight-on angle, the perspective of the piano player echoes the first time we encounter a piano in the pages of the book, the small upright piano we saw toddler Eunice reach up to play while wearing only a diaper. How far she’s come, the page seems to declare. Robinson’s artwork helps us empathize with Nina; we feel her struggles, her exhaustion, and her power. One of the ways Robinson accomplishes this feat is through the repetitive use of pianos throughout the book. Robinson varies the size, angle, and position of the various pianos in ways that create meaning and visual variety.

And then ...

After walking my fellow committee members through these nine double-page spreads, from Nina on the television screen to Nina rising from the piano on the last spread, I would hope that I had shown some examples of the ways Robinson’s artwork in Nina not only looks incredible but is distinguished in its style and delineation of theme, characters, setting, mood, and information. I would then listen carefully and take note of everything said (both positive and negative) as the discussion of Nina continues. I would begin to plan what aspects of the book's distinguished artwork could be examined during any further discussion — maybe a detailed look at how Robinson depicts faces of bystanders in comparison to our subject, or the various uses of color Robinson employees to guide readers’ emotions. With a book as rich and exquisite as Nina, finding new angles to approach the criteria would not be a challenge to any committee member intent on seeing the book rise to the top of the stack.

On January 24 we will find out what the fifteen members of the 2022 Caldecott Committee determine are the most distinguished American picture books published 2021. Nina: A Story of Nina Simone might be honored by this committee. It might not! Fifteen individuals with fifteen separate plans, strategies, favorites, aversions, and predilections will have made that determination with all deliberate thought and what I am positive will be some of the best discussions of their lives. I hope Robinson’s use of pianos will be part of that discussion, and if it is, maybe we will see some silver — or even gold — on Nina’s cover.

[Read the Horn Book Magazine review of Nina.]

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!