Picture Book, Picture Book, on the Wall...

Pictures that tell a story have been with us for a very long time. The cave painters showed us their world and their beliefs, and the Egyptians created storytelling murals in their tombs. Medieval scribes painted exquisite illustrations in their prayer books, and the painters who followed continued the storytelling on boards, walls, vases, ceilings, and canvases.

In the twentieth century, the picture-making and storytelling continue, with book illustration as one part of that tradition. Children’s book illustration, however, is a unique form and has established its own genre and personality. Within the requirements of the picture book format lies a great deal of freedom for artists. It is one of the last places to offer so much opportunity for creative self-expression and experimentation.

When I joined Cricket magazine as an assistant art director in 1972, I remember being amazed by the quality of some of the portfolios I was seeing. I had been struggling to make a living as a painter in New York but knew very little about children’s book illustration. It wasn’t long, however, before I realized that I had stumbled onto a very unusual discipline, the very best of which clearly had claims to “fine art.”

At our annual Cricket picnic in Lyme, New Hampshire, in 1973, Margot Tomes came rushing up to me to tell me that she had just been in my painting studio, and in her typical Margot fashion said, “I hate you! You do these great big canvases with all that scale and light, and I do these little scribbles!” Margot Tomes, of all people! whose work portrays such a sense of elegance and style, and whose palette is truly exceptional. For once I was speechless, but it sparked a huge debate among Margot, Hilary Knight, Tomie dePaola, Marylin Hafner, Michael Patrick Hearn, Wally Tripp, and Trina Schart Hyman until the wee small hours. And during that time I discovered how many illustrators simply didn’t think of their work as being “important” the way fine art, or “easel painting,” was.

At our annual Cricket picnic in Lyme, New Hampshire, in 1973, Margot Tomes came rushing up to me to tell me that she had just been in my painting studio, and in her typical Margot fashion said, “I hate you! You do these great big canvases with all that scale and light, and I do these little scribbles!” Margot Tomes, of all people! whose work portrays such a sense of elegance and style, and whose palette is truly exceptional. For once I was speechless, but it sparked a huge debate among Margot, Hilary Knight, Tomie dePaola, Marylin Hafner, Michael Patrick Hearn, Wally Tripp, and Trina Schart Hyman until the wee small hours. And during that time I discovered how many illustrators simply didn’t think of their work as being “important” the way fine art, or “easel painting,” was.

In the seventies, contemporary illustration, especially that done for children’s books, did not have any serious claim on the art market (unlike the more famous nineteenth- and twentieth-century artists). Many children’s-book illustrators at that time gave their work away to a special editor or art director, or in some cases to the author of the book. They certainly never thought about selling it.

Garth Williams once told me a story about the days when artwork often stayed in the hands of the publisher. He remembers walking into a very elegant party at a publishing house and being led over, by a young man who had absolutely no idea who he was, to look at four original Garth Williams illustrations. After a few minutes this young man said, proudly and in hushed tones, “These are part of the private collection and are extremely valuable — aren’t they amazing?” To which Garth replied, “Young man, you have no idea how amazed I am!” The artwork in question had simply never been returned to him.

How very different it is today. Publishers routinely return artwork after it has been reproduced, and now, due to the fact that this art may be sold again, as it were, insurance protects it while it is in the hands of the publisher or printer.

In 1978 the Original Art Exhibition opened its doors for the first time at The Master Eagle Gallery in New York City, and the byline read, “Celebrating the Fine Art of Children’s Book Illustration” — just to make it perfectly clear that such a thing did indeed exist. (This annual exhibition now continues under the guidance of the Society of Illustrators, and showcases both the original art and the books for which the art was created.) The exhibition acted as a kind of catalyst that generated a great deal of interest in the original artwork for its own sake. Within the next few years we began to see the slow emergence of galleries that represented the “fine art” of children’s book illustration.

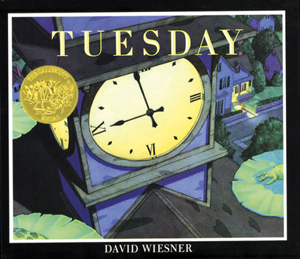

One of the first, the Schiller-Wapner Gallery, opened in 1980 in Manhattan and represented some of the top illustrators at that time, including John Steptoe, Arnold Lobel, Uri Shulevitz, Maurice Sendak, James Marshall, David Wiesner, Margot Tomes, Trina Schart Hyman, and Anita Lobel, to name just a few. The gallery was very sophisticated and quite beautiful, and the openings were elegant and well-attended. Unfortunately, the market was not yet strong enough to support such a high endeavor in such a high-rent location, and the gallery had to close its doors.

One of the first, the Schiller-Wapner Gallery, opened in 1980 in Manhattan and represented some of the top illustrators at that time, including John Steptoe, Arnold Lobel, Uri Shulevitz, Maurice Sendak, James Marshall, David Wiesner, Margot Tomes, Trina Schart Hyman, and Anita Lobel, to name just a few. The gallery was very sophisticated and quite beautiful, and the openings were elegant and well-attended. Unfortunately, the market was not yet strong enough to support such a high endeavor in such a high-rent location, and the gallery had to close its doors.

Sam and Emily Bush pioneered by opening a gallery in Norwich, Vermont, and did so well working with local illustrators that they eventually opened up a space in Boston for several years until Sam Bush died, and the gallery closed. Since then we’ve seen many other galleries open and close; happy survivors in this volatile market include Los Angeles’s Every Picture Tells a Story, run by Lois Sarkisian, and the Elizabeth Stone Gallery, in Birmingham, Michigan. Every Picture Tells a Story opened its doors in 1989 and is both sophisticated and spacious (boasting some five thousand square feet), and features a remarkable schedule of exhibitions and book signings, story hours, and political events — all aimed at keeping the gallery well attended and financially stable. The Elizabeth Stone Gallery, now in its ninth year, is also thriving. The gallery has recently opened a Web site for its clients, and continues to sponsor events similar to those at Every Picture Tells a Story. In 1994, Storyopolis joined the ranks (also in Los Angeles), and is doing well. And I hear plans are afoot for a gallery in Washington, D.C., sometime in the near future.

Finally, we are beginning to take children’s book illustration a little more seriously, and from a commercial point of view, the advantages have become financially obvious. True to the human tradition, the act of buying a piece of original art for money proves that indeed it has worth (even though we in the trenches knew it all along).

I am very much in agreement with Uri Shulevitz, who said, “There is no real distinction between ‘art’ and illustration, between old art and new art. There is only good art and bad art.” To me, the term art signifies the ultimate achievement in one’s own particular genre, where the end result has truly a unique voice — whether it be a painting in oil on canvas by N. C. Wyeth from Treasure Island, a piece from Paul O. Zelinsky’s exquisite Swamp Angel, or a picture of a smiling George and Martha by James Marshall — to name just a few of our “fine artists.”

Fine art has a dictionary definition that is quite specific: “art produced or intended primarily for beauty rather than utility” (as opposed to illustration, whose job is in its name). But when I asked Eric Brown, co-director of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York, how he would define fine art, he thought for a moment and then replied, “It’s something that changes the way you see the world.” Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak, Tuesday by David Wiesner, The Middle Passage by Tom Feelings, and Starry Messenger by Peter Sís (truly a Renaissance man) have all “changed the way we see the world,” both real and imaginary. In all of these books, each image moves forward into the next, expanding the storyline and building up to a satisfying conclusion. And each individual picture is strong enough to hang on the wall on its own, satisfying the dictionary definition as well.

Fine art has a dictionary definition that is quite specific: “art produced or intended primarily for beauty rather than utility” (as opposed to illustration, whose job is in its name). But when I asked Eric Brown, co-director of the Tibor de Nagy Gallery in New York, how he would define fine art, he thought for a moment and then replied, “It’s something that changes the way you see the world.” Where the Wild Things Are by Maurice Sendak, Tuesday by David Wiesner, The Middle Passage by Tom Feelings, and Starry Messenger by Peter Sís (truly a Renaissance man) have all “changed the way we see the world,” both real and imaginary. In all of these books, each image moves forward into the next, expanding the storyline and building up to a satisfying conclusion. And each individual picture is strong enough to hang on the wall on its own, satisfying the dictionary definition as well.

But what does the knowledge that art from a picture book may be isolated from the whole and hung on a wall do to the creation of that picture book? Artists may be thinking a little differently about the design and layout of the page, and the position of the type. Some artists are finding themselves being a lot neater with their surface texture and the way they handle their finished work.

On the other hand, we need to remember that the first job (to be utilitarian about it!) of a picture book is to be a picture book. As Trina Hyman said in her 1991 Zena Sutherland lecture, “I actually had a gallery owner tell me, ‘The clients love the art, but they all complain about those “holes” in the picture — those spaces you leave for the text.’ I heard myself reply rather stiffly, ‘That “hole” is the whole reason for the picture, you know.’”

Too, not all picture-book art works as hang-on-the-wall art. Can the picture stand on its own with much to share with the viewer? Or does it seem strangely adrift and alone? And “does it change the way we see the world?” In some instances — in some of the best, most beautiful picture books, in fact — the pictures may be so dependent on one another or on the text that, standing alone, they don’t have the voice or the power of the whole. Brave Irene by William Steig is a good example. Does Brave Irene “change the way we see the world”? Absolutely. But while the pages flow effortlessly forward, bearing the storyline to a wonderful conclusion, as individual images they seem isolated, lacking.

Too, not all picture-book art works as hang-on-the-wall art. Can the picture stand on its own with much to share with the viewer? Or does it seem strangely adrift and alone? And “does it change the way we see the world?” In some instances — in some of the best, most beautiful picture books, in fact — the pictures may be so dependent on one another or on the text that, standing alone, they don’t have the voice or the power of the whole. Brave Irene by William Steig is a good example. Does Brave Irene “change the way we see the world”? Absolutely. But while the pages flow effortlessly forward, bearing the storyline to a wonderful conclusion, as individual images they seem isolated, lacking.

As we approach the new century, we now have a definite market for the sale of original picture book illustration, and a great deal of respect for the art itself as it stands alone. A great many illustrators are now represented by galleries — and doing extremely well in the sale of their work. William Joyce has seen a great deal of commercial success, and currently the works of Jerry Pinkney, Jules Feiffer, David Shannon, Mark Buehner, Gary Kelley, Kevin Hawkes, Alexandra Day, and Giselle Potter all have sure-fire appeal to the general public. And the canvas is still broadening: as we see children’s book illustration handled as fine art in the marketplace, big business in the form of Bell Atlantic features Wild Things scampering across our television screens. (Now, Wild Things are personal, and I am torn between “What fun!” and “Leave our childhood memories alone!”) One thing is certain: children’s book illustration enters the new century as a much more complex undertaking involving a multitude of commercial possibilities for continuing usage. However, in the beginning was the book — the raison d’être for the illustration — and it’s no accident that the most successful illustrations are inspired by an outstanding story. As Barbara Cooney reminded us all in her Caldecott acceptance speech for Ox-Cart Man in 1980, “In the beginning was the word”; she continued to say that without the author Donald Hall, she would not have been standing there that day.

So let us celebrate the fine art of the book, which continues to be a springboard for the imagination, a treasure trove of art, and a place to discover our world and our sense of humor.

From the March/April 1998 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!

Emily Bush Jones

Thank you for this article which I have just seen in preparation for a presentation for a lecture on children book illustration in Bush Galleries. Thank you Dilys for bringing back happy memories Sam and I shared with you and others in loving this special art.Posted : Mar 29, 2018 12:20