2018 School Spending Survey Report

What’s New About New Adult?

Coming of age.

Let’s discuss what we mean when we compare YA and NA. First there’s what we’ll call Traditional YA, published by children’s and young adult publishers, featuring teenaged protagonists, and aimed at middle school and high school students. In the past few years, Upper YA has emerged as a subset of Traditional YA, with protagonists who are just out of high school or even in college. Sarah Dessen’s and Lauren Myracle’s most recent novels (The Moon and More [Viking, 2013] and The Infinite Moment of Us [Amulet/Abrams, 2013], respectively), for example, take place during the summer after senior year. As fans of these popular authors have grown up, the writers have kept pace by nudging their protagonists closer to adulthood.

Let’s discuss what we mean when we compare YA and NA. First there’s what we’ll call Traditional YA, published by children’s and young adult publishers, featuring teenaged protagonists, and aimed at middle school and high school students. In the past few years, Upper YA has emerged as a subset of Traditional YA, with protagonists who are just out of high school or even in college. Sarah Dessen’s and Lauren Myracle’s most recent novels (The Moon and More [Viking, 2013] and The Infinite Moment of Us [Amulet/Abrams, 2013], respectively), for example, take place during the summer after senior year. As fans of these popular authors have grown up, the writers have kept pace by nudging their protagonists closer to adulthood.New Adult — aimed at an adult audience but with strong appeal for teen readers — has recently garnered much buzz. Story lines tend to follow the contours of contemporary genre romance novels, but starring younger characters. NA initially took hold in the self-publishing world (the quality of writing varying wildly), and these books found an audience of dedicated, loyal, even ravenous readers. Authors could write stories that satisfied their fans and publish them quickly. With such a proven fan base, it didn’t take long for traditional publishing houses to take notice, seeking out and acquiring some of these high-performing books and trying their own hands at New Adult. The actual term “New Adult” sprang from a contest held by primarily adult publisher St. Martin’s Press in 2009, seeking manuscripts featuring eighteen-and-older characters that read like YA but would be published and marketed for adults.

Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Penguin Random House are now printing originally self-published e-book titles by popular NA authors including Abbi Glines, Colleen Hoover, and Jessica Sorenson under both YA and adult imprints. In some cases, this has led to slightly different content for different audiences. For example, Glines’s Vincent Boys series, originally self-published, was acquired by the YA imprint Simon Pulse in 2012. Simon first published it as an e-book, with hardcover and paperback editions to follow. Soon after, the publisher released what might be best termed “The Full Vincent”: The Vincent Boys Extended and Uncut in e-book formats, available only from online retailers. The publisher has labeled the Extended and Uncut editions as appropriate for readers “over seventeen.”

Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Penguin Random House are now printing originally self-published e-book titles by popular NA authors including Abbi Glines, Colleen Hoover, and Jessica Sorenson under both YA and adult imprints. In some cases, this has led to slightly different content for different audiences. For example, Glines’s Vincent Boys series, originally self-published, was acquired by the YA imprint Simon Pulse in 2012. Simon first published it as an e-book, with hardcover and paperback editions to follow. Soon after, the publisher released what might be best termed “The Full Vincent”: The Vincent Boys Extended and Uncut in e-book formats, available only from online retailers. The publisher has labeled the Extended and Uncut editions as appropriate for readers “over seventeen.”The rapid growth of NA, its surge in popularity, and the willingness publishers have shown to edit and format material differently to capture different audiences make us wonder about the implications for Traditional YA literature. What makes a YA book truly a YA book and not something else? Is it — as the Vincent Boys publishing history may indicate — that NA simply includes more explicit sex scenes than what is found in YA?

Some New Adult authors and fans argue that “coming of age,” which has long been considered the province of YA, is properly a twenty-something experience. They argue for two phases of coming of age: the emotional preparation for the journey being represented in YA, then the journey itself showcased in NA. NA writer Sommer Leigh suggests that “the heart of YA is the coming-of-age story about a teen’s first step towards deciding who they are and what they want to become. The coming-of-age story in New Adult is about actually becoming that person. Or not, as the case may be.” In short, coming of age is a process that takes place over many years, so it makes sense to stretch it out across both YA and NA.

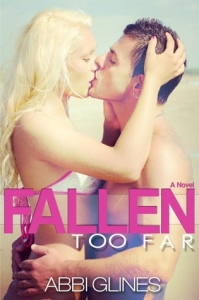

To illustrate Leigh’s point, let’s look at three books: Sarah Dessen’s Lock and Key (Viking, 2008), Lauren Myracle’s The Infinite Moment of Us, and Abbi Glines’s Fallen Too Far (self-published, 2012), as representative examples of Traditional YA, Upper YA, and NA, respectively.

In Lock and Key, high school senior Ruby goes to live with her older sister and brother-in-law after her neglectful alcoholic mother abandons her. Living with Cora and Jamie, Ruby learns some hard truths about her family. She also makes new friends and begins a prickly-but-swoony romance with the cute boy next door. This book fits squarely within Traditional YA, with the lead character facing her own challenges and finding and letting go of an ephemeral romance. The issues here feel age-appropriately internal and self-contained: Ruby’s main concerns pertain to high school and her immediate family.

In Lock and Key, high school senior Ruby goes to live with her older sister and brother-in-law after her neglectful alcoholic mother abandons her. Living with Cora and Jamie, Ruby learns some hard truths about her family. She also makes new friends and begins a prickly-but-swoony romance with the cute boy next door. This book fits squarely within Traditional YA, with the lead character facing her own challenges and finding and letting go of an ephemeral romance. The issues here feel age-appropriately internal and self-contained: Ruby’s main concerns pertain to high school and her immediate family. The Infinite Moment of Us takes place during the summer between the end of high school and the beginning of the grand adventure of grown-up life. High-achieving good girl Wren is drawn into a sweet and intense romance with quiet loner Charlie. Conversations, dreams, and anxieties relating to life beyond senior year are the main focus here, and they unfold alongside Wren and Charlie’s frank sexual awakening.

The Infinite Moment of Us takes place during the summer between the end of high school and the beginning of the grand adventure of grown-up life. High-achieving good girl Wren is drawn into a sweet and intense romance with quiet loner Charlie. Conversations, dreams, and anxieties relating to life beyond senior year are the main focus here, and they unfold alongside Wren and Charlie’s frank sexual awakening. Fallen Too Far follows nineteen-year-old Blaire, who skipped dating during her earlier teen years to nurse her mother through a terminal illness. She makes up for lost time by embarking on a journey of desire with Rush, her tortured, far-more-experienced twenty-four-year-old stepbrother, whom she recently met for the first time. Although Myracle’s The Infinite Moment of Us does feature a steamy romance, it’s not strictly a romance novel. It is also concerned with friendship, the choice of attending or not attending college, and more, and Wren’s story ends at the end of this book. By contrast, Fallen Too Far, the first book in a series, focuses squarely on romance and sexuality as Blaire’s primary route toward adulthood. Rather than resolving neatly at the end, the plot grows more tangled with revelations of family secrets, and concludes with a tantalizing cliffhanger leading straight into a sequel, Never Too Far. Unlike Dessen’s and Myracle’s novels, Blaire’s story continues into her adulthood.

Fallen Too Far follows nineteen-year-old Blaire, who skipped dating during her earlier teen years to nurse her mother through a terminal illness. She makes up for lost time by embarking on a journey of desire with Rush, her tortured, far-more-experienced twenty-four-year-old stepbrother, whom she recently met for the first time. Although Myracle’s The Infinite Moment of Us does feature a steamy romance, it’s not strictly a romance novel. It is also concerned with friendship, the choice of attending or not attending college, and more, and Wren’s story ends at the end of this book. By contrast, Fallen Too Far, the first book in a series, focuses squarely on romance and sexuality as Blaire’s primary route toward adulthood. Rather than resolving neatly at the end, the plot grows more tangled with revelations of family secrets, and concludes with a tantalizing cliffhanger leading straight into a sequel, Never Too Far. Unlike Dessen’s and Myracle’s novels, Blaire’s story continues into her adulthood.What do these subtle nuances in the definitions of and themes explored in books for three distinct (but often overlapping) audiences mean? It depends who you ask. YA sections differ from library to library; some contain books for readers twelve and older, others books for fourteen and up. In some libraries, the YA section is read primarily by middle schoolers, with high schoolers borrowing from the adult section instead. Abrams has published The Infinite Moment of Us as YA; therefore it is YA, according to the publishing industry. But perhaps a particular librarian buys it for her collection and decides it fits in better with her adult books because of the not-super-explicit but still frank depictions of sex. Is it now NA for that community? Who gets to make the determination of what a YA book truly is? And what about the definitions of individual readers, who may not be aware of or care about this brouhaha in publishing and librarianship?

If you’re left with more questions than answers, you’re not alone. Some see NA as a fad that will disappear by next year. Others see it as an example of increased niche stratification of books based on age that may well lead to “Middle Age Lit” and “Empty Nester Lit.” Others think that it will stick around; that, like its protagonists, it’s still coming of age. Will it remain primarily contemporary romance? Will it cross over more vigorously into genres like fantasy, horror, mystery, and literary fiction? There aren’t definitive answers to be had as New Adult continues the process of becoming whatever it’s going to be. The discussion should and will continue.

New Adult Resources

ReadAdv (The Reader’s Advisory Twitter Chat): http://readadv.wordpress.com/new-adult-resources/

Dear Author: http://dearauthor.com/tag/new-adult/

Heroes and Heartbreakers: http://www.heroesandheartbreakers.com/tags/New%20Adult

NA Alley: http://www.naalley.com/

Facebook’s New Adult Book Club: https://www.facebook.com/NewAdultBookClub

More Upper YA Titles

Scowler (Delacorte, 2013) by Daniel Kraus

The Disenchantments (Dutton, 2012) by Nina LaCour

The Piper’s Son (Candlewick, 2011) by Melina Marchetta

Fangirl (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2013) by Rainbow Rowell

Something like Normal (Bloomsbury, 2012) by Trish Doller

Uses for Boys (St. Martin’s Griffin, 2013) by Erica Lorraine Scheidt

Roomies (Little, Brown, 2013) by Sara Zarr and Tara Altebrando

From the January/February 2014 issue of The Horn Book Magazine.

RELATED

RECOMMENDED

ALREADY A SUBSCRIBER? LOG IN

We are currently offering this content for free. Sign up now to activate your personal profile, where you can save articles for future viewing.

Add Comment :-

Be the first reader to comment.

Comment Policy:

Comment should not be empty !!!